PAUL KOLKER

Paul Kolker: The Best Is Yet To Be…

Starry Nights Ahead

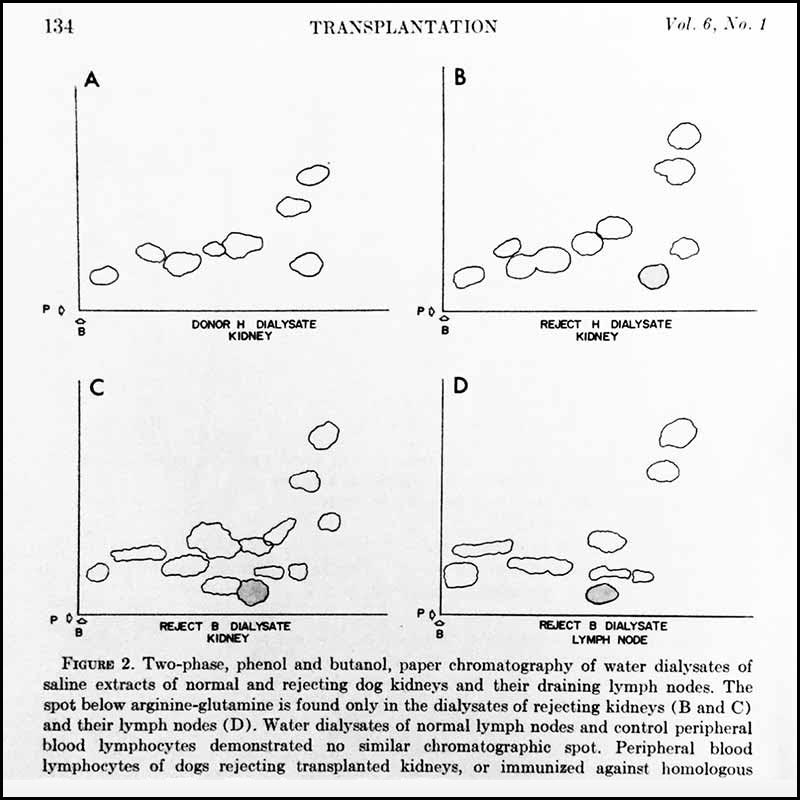

During the Fall 1965, working at the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in Boston and Harvard Medical School as a Fellow in Transplantation Surgery, I along with Gus Hampers and Ted Hager, while successfully testing for and identifying rejection antibodies, stumbled upon the discovery of certain low molecular weight immunologically active polypeptides. They are depicted above in the gray spots of my ink on paper drawings of chromatographs of dialysates of rejecting dog kidneys and are absent in the controls. In 1974 Stanley Cohen characterized and named these small immunologically active polypeptides ‘cytokines.’ Today the so-called ‘cytokine storm,’ a ferocious immune response, is associated with the lethal effects of COVID-19.

On Monday, March 9, 2020 we closed the doors to our exhibitions because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The following day, I met with Jeff and Bryan, and provided Dan with appropriate archival and exhibition installation views, including a check list of works, so that viewers could safely and virtually visit the exhibitions on our website by clicking on Paul Kolker: Exhibitions.

I have remained at my Long Island home since March 11 sheltering myself, along with my daughter Shani and my Great Pyrenee-Lab-mix, Tenley; shopping safely online; preparing meals and exercising regularly; and working day and night in my reappropriated studio in preparation for my next exhibition, ‘The Best is Yet to Be,’ inspired by Robert Browning’s aspirational poem, Rabbi Ben Ezra.

Jeff and Bryan were furloughed the following week, with the hope that both they and I might return when the Chelsea art district reopens. My creative paradigm is to research a subject matter, including its art history; create new relevant works in my signature-style and curate their exhibition in a manner which tests the viewer’s perception like a controlled brain-science or psychology experiment does. Not willing to let go of my almost twenty years’ practice in exhibiting my art as experiment to the public at 511 West 25th Street in Chelsea adjacent to the HighLine, I had applied for a SBA loan, received a confirmation number and still await a reply.

Our Chelsea space, the PAUL KOLKER collection, has already been in lock-down for more than fifty days in compliance with governmental social distancing measures and other public health agency guidelines to mitigate disease progression over time by flattening the curve of hospitalized patients so as not to overburden New York City healthcare systems’ available resources to care for all COVID-19 patients. As a result of this pandemic the general public has become more aware of our world of evidence based science as contrasted to anecdotal experiences. Such evidence is derived from controlled experiments whose outcomes are statistically analyzed and peer reviewed; i.e. corroborated by other experiments performed by other scientist experts. These experiments are also called research studies or clinical trials.

Medicine is also an art which is dependent on insights and gut feelings. I call these insights and feelings ‘perceptions’ because they are informed by certain physical diagnosis subliminal visual and other sensory prompts derived from specialized training in medical school, residency and practice. These perceptions are the same that artists and curators derive their creative and curatorial vibes from. Some call it a smell test. Others, an instinct. But clearly, whatever this gut feeling is, it remains far beyond that which we see in the patient’s eyes or on her face. It is a lightbulb aglow in our mind illuminating an extrasensory perception of diagnosis. Perhaps, that is why during the past several decades medical academicians introduced fine arts studies with exhibition visits into most medical school curriculums.

Both in art as in science peer review is mandatory. An exhibition serves to engage a myriad of beholders with all sorts of perceptions in dialogue with the artist and her works. As in law, in the arts the reasonable person standard prevails. All beholders of art and its exhibition become the measuring instruments for art as experiment!

Human perception is a science studied in vision and neuroscience laboratories. Experimental psychology, which studies human behavior, is also a science. Our perception of art affects our mood; while our mood also affects how we perceive a work of art. And certainly our COVID-19 lock-down affects our mood. In addition, perceptual interaction is communicative, like a language replete with innuendo and meaning… and has therefore been rendered dialogic according to Mikhail Bakhtin’s ‘The Dialogic Imagination.’

Dialogic is also different from the Platonic or Hegelian dialectic, wherein thesis and antithesis arguments are resolved in a binary process called synthesis. Many of us remember how difficult it was to write and advocate our dissertations without the give and take of the dialogic which relies on the implied intent of the spoken words; our perception of the meaning of those words.

Dialogical perception, my neologism, references the interaction of an individual’s perception with those perceptions of a larger group; transporting us to a place beyond our isolated selves. It acculturates our humanity and our caring for others as well as ourselves. We perceptually become linked by the dialogical glue of Martin Buber’s hyphenated I-Thou relationship. This socially interactive force is extant as humankind’s dialogue. It keeps us together as a family, community, nation and world. We are not alone, even though today we remain sequestered at home. Our relationships are hyphenated to others whom we search out in real-time using our wireless or cable communication devices; or otherwise access through the internet, television and even daily print-newspapers. We can FaceTime and even Zoom our conferences; including holocaust memorial events, seders, Easter Sunday dinners and a video visit with our doctor. We may also visit virtual online art exhibitions in a manner comporting with physical distancing to mitigate the contagion of the pandemic, while remotely and safely cultivating our aesthetic feelings… as well as the connoisseurship and creativity which drives us.

This urge to reach out during our lock-down is also dialogic. We are like a virus whose survival depends on its becoming a part of others; me becomes we. And vice versa. We are locked-down and yet we are locked together, metaphorically, arm in arm; but with social distancing. We crave social interactions on Facebook, Twitter, WEChat, instagram, LinkedIn, YouTube, Constant Contact and more. We are dialogically interactive social beings who miss the societal norms of congregating in churches, mosques and synagogues; eating at restaurants; attending lectures, symphony, opera, ballet and conferences; exhibitions at art fairs, museums, auction houses, galleries and artist studios like mine. Lacking the foregoing, our lock-down ‘pictures at an exhibition’ have become the graphics of Drs. Anthony Fauci and Deborah Birx portraying an analog plot of a wave of COVID-19 daily confirmed cases and another of the effective reproduction numbers called R. If the statistician’s R drops below 1, the mitigation effects of the lock-down are working, the virus has fewer hosts to invade and the epidemic shrinks. But, regretfully, in New York City, which is the epicenter of the universes of art, finance and the pandemic, R is not there yet.

In the Spring 1988, while in law school, I wrote a paper, ‘How Safe is Safe Enough?,’ in satisfaction of my healthcare law course under the direction of Professor John Regan. My paper reflected on legal and ethical issues relating to the AIDS epidemic. Included were discussions about the risks and benefits of treatments which affected, beyond a small cohort of about 1500 infected patients at the time, the entire worldwide medical community of caregivers and their families. As a member of the latter group, I as a heart surgeon was one who figuratively ‘bathed in blood’ almost daily. Moreover, for privacy reasons, I could not find out which of my patients had the highly infectious disease; so we surgeons all double gloved and otherwise flew on a wing and a prayer; plus lots of hand washing and showering.

But the lessons we learned all-too-slowly after thirty-five years of global AIDS were to test, track and treat. When I had written ‘How Safe is Safe Enough?’ our nation was emerging from a recession, plagued by AIDS and overwhelmed by Iran-Contra. Reflecting today on my law school research, our federal and state governments in 1988 failed to intervene in the manner of today’s most heroic of governmental decisions made by President Trump and Governor Andrew Cuomo and other governors; sacrificing an economy for our lives. That is why on March 9, 2020 I was a first adopter of COVID-19 mitigation of human to human transmission; imitating Isaac Newton’s flight from plague-ridden London to the countryside in 1665. I temporarily closed the doors to my studio in Chelsea; and immediately began working at my Long Island home on my next show, ‘The Best is Yet to Be.’ It is about George Sarton’s Introduction to the History of Science from Rabbi Ben Ezra to Roger Bacon; that same Rabbi Ben Ezra sung by Robert Browning in his poem which I have dialogically transformed from words into paintings, light sculptures and videos of constellations of dots; all aspiring towards the starry nights ahead!

— Paul Kolker – April 27, 2020